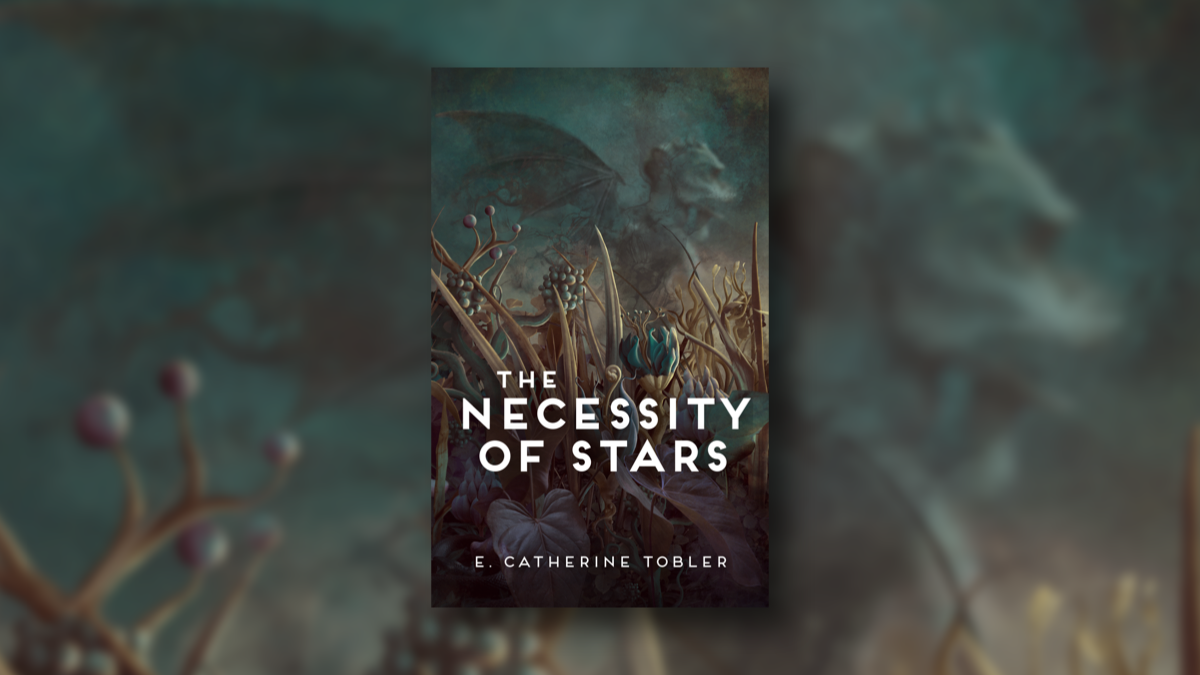

An Excerpt from A NECESSITY OF STARS

An excerpt from The Necessity of Stars by E. Catherine Tobler:

When I don’t remember my name, I will remember this.

Tura was the color of a Normandy sky, ten-thirty in the evening. A June. Darker in the east, lighter in the west, the echo of a sun-bright day refusing to fade entirely. The length of them rioted with storm clouds, a blue-black horizon sinking into starless murk. Their naked torso was slashed from shoulder to thigh with the colors of the Milky Way, eggplant blooming from the blue, spilling into apricot and cream before blue swallowed the light again. They would have been invisible but for the moon glowing.

Stars glowed in the valleys of Tura’s palms, narrow palms bearing only three fingers. A sort-of thumb, though longer than any I’d seen, and two longer fingers. The coal black nails glittered with stardust. You look like you’ve fallen through a nebula, I whispered, and Tura laughed. It was the sound of an overloaded freight train, low and rumbling, moving through water if you listened long enough, with a hiss at the end. I listened long enough. I did fall through a nebula, and another, and yet one more, Tura said as their hand enfolded my bare shoulder.

This was how they were with the trees, skin to skin, Tura told me. They pressed their skins together and became. But then, Tura realized my skin was nothing like a tree. We stood silent in the moonlight. Tura’s fingers played over my smooth skin, and their eyes met mine. (If their body was the sky itself, their eyes were planets therein, thousand-ringed Saturn and blue Neptune.) I have never touched a human, they said. They had touched many trees, but never a human, until now, and they asked if they could.

I wanted those star-hands on my skin.

Tura told me I was the color of Eta Carinae, white hot and blown wide open. Red wavelengths, ultraviolet wavelengths, I asked which, but Tura’s hand brushed over my mouth to silence me. The darkness of them tasted like pine, like bark. Five million more times luminous than your sun, they said as their thin hands slid down my arms. Circumpolar, always above the horizon, pulling the eye back and back again. Variable, but constant. Supernova.

Their fingers found every ridge and valley I possessed. Every scar and pucker—I had been an adventurous young lady, if no more. Their fingers explored the steps of my spine, the bow of my collarbone. Tura asked me to name every piece of myself so they would understand, so they would know me the way they knew the trees. The shoulder, the breast, the knee. The freckles, the wrinkles, the marks of age. When a touch provoked a blushing response, the heat of my skin making my pleasure apparent even in the moonlight, Tura wanted to understand the why and the how—trees did not do this—and I said stars did not explain themselves, they just were.

When I don’t remember my name, I will remember this.

†

When I rose one June morning to discover a dark shadow slashing across my garden, I thought that the collapse had begun. We had done what we could. But this was no gradual death; I didn’t know what had happened, but it was something terrible. It looked like the ground had been scorched, that something had plummeted from the sky and hit the edge of my lily pond. A meteor strike? I hadn’t heard a blessed thing!

The damage was so concerning, I didn’t hesitate. I dressed more quickly than an old woman has a right to, and fled down the stairs and out the kitchen door. I should have grabbed a coat, for the day was chilly, the air damp, even though it was a June. I didn’t even have shoes on. My heart would not calm itself, and I thought this is how it ends, I shall run into the garden and my heart will give out, and the touch of the cool grass will be the last thing I know.

Only I couldn’t remember the word grass.

I looked at all that green, and how the smudge of black lay upon it and could not remember grass. I plunged into it, the green damp and cold beneath my bare feet, heading for whatever had blackened the ground, and the blackness moved and I recoiled.

In that instant, the shadow (is that what it was?) looked normal. From this angle, it was only the shadow of a long branch ruffled with leaves, extending over the pond. I glanced up to see the very branch that cast the shadow, leaves moving in the cool breeze just as they should. But beyond the branch and its tree, the sky was a flat gray. A gray that covered the sun thickly enough that no shadow should fall anywhere.

A look told me I was right—I wasn’t imagining it, I had not forgotten how shadows and light worked. Tree shadows spread over the pond, but anything that wasn’t a tree—every flower, every bush—was without shadow. Only the trees had shadows and they were all normal now, as if those shadows had become aware of me, and had snapped back into the places they knew they should occupy.

There have been many moments where I considered what I do and do not know. Words have fallen from my vocabulary, and so too have events left me entirely. The past is more vivid a thing than the present—I remembered being twenty and in love so clearly, it was as if it happened yesterday, whereas yesterday could often be a blur. If I did not share the day with someone, it could be even more challenging to remember. What did I eat? What did I do? Did I wander into town?

The iris trembled in the wind, and I became aware of exactly how wet it was, standing there in my bare feet. I straightened up and looked around again. Only tree shadows. Were my eyes failing me? I rubbed them but the shadows did not vanish, nor did any others appear; it was too cloudy a day.

I exhaled.

“All right,” I said. I wouldn’t call myself lonely—would anyone truly admit it?—but hearing my own voice often helped remind me where I was. Who I was. Now, I addressed the shadows.

“My name is Bréone Hemmerli, and I am the Special Representative of the Secretary-General of the United Nations.”

I didn’t know what I expected, but nothing happened.

Often, in diplomatic negotiations, I found myself in such circumstances. Neither side will want to begin, because going first exposes a perceived vulnerability. No one wants to admit they want something so dear—and yet, by coming to the table, they have already admitted such.

This was not necessarily a negotiation, because I may well have imagined the entire scene—maybe there was enough light for shadows, so the trees were fine. But nothing else carried a shadow and unless they had all been Peter Pan’d into otherness, something was amiss.

I thought to get Delphine, to see if she could see what I saw, but I also didn’t want to leave the garden, because the idea that I was imagining it all was strong. If I brought Delphine and she didn’t see that only the trees had shadows, something was amiss with me. And if she did see the strangeness, what did it say of our world?

It was curious what a body will grow accustomed to—staying in a single room all day because everything was where it should be, for instance, rather than venturing into a garden where things could so easily be improper.

I had loved the garden at first sight, but had avoided it because it had come to frighten me with the way it did not change. That is the truth of it, isn’t it? I didn’t only stay inside by the warm hearth. I stayed inside because I could control that environment. I knew where the cups went and where the blankets were and where I had written myself notes of things to remember. Let us not linger over the fact that sometimes I forgot how doors worked and had once trapped myself inside because I could not remember pull instead of push. Nor that I could not bring myself to write those words down. To admit the lack.

Neither was it easy to admit to the fear I had begun to harbor of the garden, given its riotous life. Droughts did not stop the flowers; they unfurled in sun or rain. The trees did not break in random snowstorms, but only seemed to dig themselves in deeper so they might grow thicker.

Sugden told me the land had once belonged to Eleanor of Aquitaine—he said the land was magic, because she had built it into the dirt, into the roots, into the very structure. He spoke of her as though she were a witch, but he did this often with women, turning them into something he could never understand, as if they were not people just as him. I did not know if this was true—Irislands sits outside Rouen, and if Eleanor of Aquitaine ever came this far north, I didn’t know.

It was easy to envision her beneath the trees, walking the paths worn into the undergrowth. Easy to dream her in the halls of the house, staring down at the remains of the moat that circled the walls. Sometimes I pictured her on her knees, digging in the dirt, digging until the soil was hard beneath her nails. I often had trouble remembering the facts of my days, so it was easier to make my own, to picture Eleanor with the softly blooming iris and aquilegia, so that I could remember it all as her creation. Someone had made this space, who better than her? Without a creator, the garden felt unmoored. Surely it had been composed with the same care as Monet’s Giverny, every house window framing a singular painting.

To imagine her hands cupping the pale petals of the Félicité et Perpétue roses was to remember that the nearby garden gate the roses tumbled over was the path toward Delphine’s hands next door. To think that Eleanor had washed the horizon with the gently blooming trees, arranging the pink, the cream, the lavender, with glimpses of sometimes-blue sky between was to reassure myself that people had done good works and could do them again.

But the darkness.

The—

I could not remember the word.

The darkness moved again and my chest hurt and I decided that if this was it, it was fine. Delphine would find me in the grass and she would wonder over my bare feet, but she would call the proper people and they would bundle me away into the—

“Shadow,” I said, remembering what it was called as the shadow rose from the ground. It took on dimension, like a cloud rising from the grass. It bubbled up as if it had a thunderstorm in its belly, and I could all of a sudden pick out shapes and forms from the darkness. It was not merely a shadow, but contained a face.

I took a step back, the cold grass prickling my foot. I could not breathe and I could not think as the face emerged from the shadow. It was not human, but it contained enough similarities that I found myself picking out eyes, a nose, a mouth that was more pincer than lip. A broad shoulder curved into a broader wing, wings the color of oil on black water—the more I looked at the figure, the more it felt made of black pond water and not shadow, because it was fluid, perhaps trying to contain itself to this form. Branch-thinarms tapered to even thinner hands, with only three fingers, one perhaps a twice-long thumb.

The figure moved toward me, and I moved away, and it felt like a dance. I didn’t feel pursued so much as I felt studied, and I studied in turn, because I knew I would not run away. I didn’t feel I could run—this body has not been that reliable—but I didn’t want to run, despite not understanding what I was looking at. I had never been one to run, of course—I had met with Prime Minister Johnson and First Minister Campbell, and once upon a time they said only Bréone Hemmerli could go to the Kingdom because only I had been able to untangle what each side truly desired. (It wasn’t so complicated or difficult to respect a peoples’ inherent worth, after all.)

“My name is Bréone Hemmerli,” I said into the morning air, “and I am the Special Representative of the Secretary-General of the United Nations.”

At the sound of my voice, the figure took a step back. I took a step forward. I felt curiously small, because the shadow was broad and tall, even if the arms were oddly thin—tree branches, I thought, and the idea stole my breath, because tree shadows, but the shadow moved again and I moved too. The shadow moved parallel to the pond, the water directly behind. I could not see through the shadow—the figure was solid, whatever else it might be. It reached, not for me, but for the nearest tree, which moved from its grasp, which fell apart into a second shadow form, that slithered through the iris beds and away. The first shadow stared at me.

It felt strangely accusing, and I was back to not breathing, because I was staring into eyes unlike any I had ever seen. One burned blue, the other bright, the iris encircled by rings. Ironic, that—the iris of the eye, the iris of my garden. My brain raced to make sense of it all, and I could only remember that I was barefoot—of all things to come back to—and it was then my body finally failed me. I fell to the grass and could not breathe, could not think. There was a dark weight upon my chest and then nothing more until Delphine slapped me across the cheek.

The canopy of trees behind Delphine’s head was so bright. Watery sun tried to pierce the gray sky, but could not quite. I sat up much more quickly than I ever should have, and promptly vomited into the grass. Delphine’s hands fussed with me, and I couldn’t understand what she meant to do, only that I didn’t want her doing it. I pushed her hands away and away again, because she would not stop.

“Bréone—Stop it, Bréone—Bréone....”

It was then I realized she was crying, and I stopped trying to push her away. I saw she’d brought the cart with her, and I helped her get me into it—we joked that we would be wheeling each other about one day, and here it was. My backside was damp from the grass, but Delphine didn’t care. She hauled me up and into the cart, and then toward the house. The house—why had I been outside the house?

I couldn’t remember.

##

The Necessity of Stars by E. Catherine Tobler is part of the pre-sale campaign for the 2021 Novella Series, on Kickstarter in May 2021. Publication Date: July 20th, 2021. Questions: admin@neonhemlock.com